Herald Article "Clinicians, Faith Leaders Discuss Grief, Healing"

Emphasize Need for People To Support One Another In Handling Loss

January 15, 2026

By Maryellen Apelquist

Grief never ends; it’s ever-changing. The wound created by the loss of a loved one heals with time, but not wholly, usually becoming less raw as it reshapes who we are.

We go on as best we can. There are bad days, and better days. Days when “we can carry grief and joy,” explains Nancy Kenyon Richardson, a licensed clinical mental health counselor (LCMHC) who lives in Randolph Center.

“I have learned that grief and joy can walk together. People are so complicated. We can carry opposing emotions at the same time.”

The therapist, who owns the Psychological Wellness Clinic in Stowe, also speaks from personal experience. Richardson lost her son, Kevin Kenyon, when he was 25 years old, killed by a train as he took a shortcut along his walk to work. Wearing noise-blocking earbuds, Kenyon didn’t hear the locomotive coming.

This past Christmas, the 11th since her son died, marked the first one Richardson and her family were able to spend at home.

“Grief is hard—it’s hard even when you’re a professional,” she said during an interview earlier this week.

Richardson talked about grief as someone once described it to her: “If you put a ball in a box and everywhere that the ball touches the side of the box—it barely fits in— it’s touching it all over, everywhere, it hurts so badly, the grief. Over time, the ball gets smaller, but every time it rolls and touches one of the sides, it still hurts just as much.”

The conversation with the clinician came after multiple deaths by suicide across the White River Valley, all unrelated, over the span of a few weeks, and as community members have come together to mourn. She said connection is key to supporting each other and our community “during the grief process, but also to prevent further tragedies like this.

“The biggest protective factor is connection.”

Having a “trusted adult is huge for anyone, youth or adult, to feel seen, believed, and to not have their feelings minimized.”

Richardson, also a deacon at Bethany Church in Randolph, emphasized the importance of routine check-ins, having a predictable structure, and making safe spaces to talk.

Suicide, she said, is a public health and community issue, “but it’s very rarely about a single event. It’s this interaction between vulnerabilities and it’s often mental health, neurodivergent, trauma depression, all those kinds of things.”

Richardson explained that, after a suicide, grieving people may search for answers and point to environmental stressors, such as bullying or isolation.

“But there’s almost always these other things involved— trauma, depression, other mental-health issues—so when we’re looking at the grief process, we have to consider all of that for the community,” she said.

The clinician noted that because loved ones want answers, they can “latch onto one of the factors” and “unintentionally increase guilt in peers,” creating “a misleading narrative that suicide is a reaction rather than seeing it as a preventable crisis.”

One of the most difficult parts of the grieving process, Richardson noted, is facing the unanswered questions, especially among adolescents, and that “we want to make sure we never frame bullying as the only cause.

“That can end up leading others to make that same choice. We want to make sure that we’re getting messages out there to counter that. Adolescents are still developing impulse control and emotional regulation, so they’re at a higher risk when someone is lost by suicide in their sphere, whether that’s an adult or another child. The prevention is very possible and really the key factor.”

Randolph resident Tom Harty, a funeral director with Day Funeral Home and longtime pastor of the United Church of Bethel, has for decades helped individuals and families as they grieve. He’s also lost a loved one, his brother, to suicide, and has spoken openly about his personal experiences.

Like Richardson, Harty emphasized the importance of human connection. He also noted that we each experience grief differently, and therefore “need to talk and feel our way through it.

“And that means you cannot do it in isolation. You simply cannot do it in isolation.

“The other thing that I always worry about, especially in cases of tragic death, young death, is that the persons involved— oftentimes it’s a parent—just cannot come to terms with it,” he said, “so they want to do things like not go through the motions, not have a service, not bury the ashes. They want to create a shrine in their home, or they keep a bedroom the same. Their fear is, usually, ‘I don’t want to forget them, therefore I have to put them in priority every day,’ and that’s dangerous territory.”

Harty said we might look to how people grieved a century ago, when small towns and church communities provided not only an outlet for feelings of grief, but also a way to help community members understand those feelings.

“Because they were taught the stories that humans had used to adapt to grief and to pain and to suffering. We have less of that societal understanding now. We’re more individualistic, and so that affects” how we grieve, he said.

Harty also spoke of the season.

“Nobody should be alone at this time of year. It’s cold, it’s dark, and then all it takes is a complicated incident or the kind of grief we’re talking about, and we have people that decide to, you know, end their lives. And that creates for those families an even more complicated grief, especially in light of social media.”

He said that as a global society, in general, “I think we feel [grief associated with such tragedies] more so because we haven’t yet developed the societal norms not to, or the physical norms not to, or the tools to use not to feel overwhelmed.”

Provider Perspective

Courtney Riley, a pediatrician at Gifford, likewise brings personal experience to the conversation about grief. She lost her 23-year-old sister five years ago, to a heart attack, and knows intimately grief’s nonlinear nature.

“It spirals and circles and feels heavy at times and lighter at times, but it never really goes away,” wrote Riley in an email to The Herald.

The doctor covered ways everyone can support each other through grief: by talking about the person who died, and by being present.

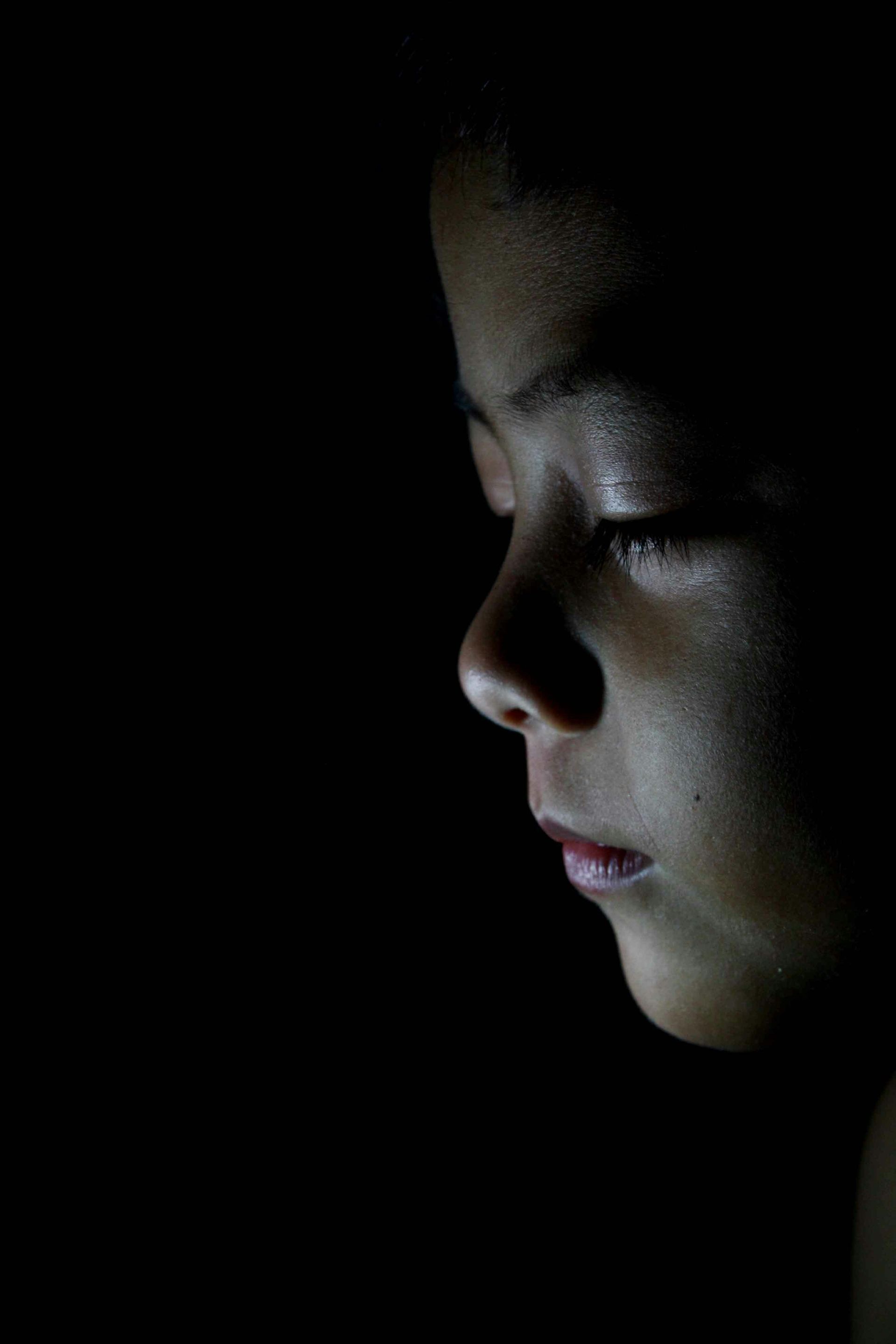

“Sometimes people shy away because they don’t know what to say. You don’t have to say anything at all. Just being present helps the person know they’re not alone in a dark hole.”

The doctor also suggested avoiding phrases like “reach out to me if you need anything.”

Rather, identify a way to help, and follow through.

“Drop fresh groceries off at the front door or come in and do the dishes and laundry,” she said. “Stay as long as the person wants, or you can, and then leave. It’s so hard to ask for help and not everyone will even know what to ask for or want to ‘burden’ other people.”

Like Harty, Riley noted the importance of not avoiding grief: “Ride the wave. Feel the feelings as deeply as they are for as long as it is present. When we try to suppress the feelings, it can come out in other ways.”

She likewise emphasized giving feelings the time and space they need. “There’s no timeline you have to meet, or no right or wrong way to grieve. We put unnecessary pressure on ourselves sometimes to ‘move on.’”

When unsure what to do next, she said simply, “drink water.”

Grieving with Kids

Riley talked about the importance of letting children see us cry, “to see adults feel their feelings.”

“What a powerful lesson it is for our children to see us fall down to our knees in grief, be fully present with a feeling, and then be able to stand back up!”

She also provided the following guidance for speaking with children during times of grief:

• Be open and honest. Children pick up on what’s happening around them, and they are trying to figure out what’s going on.

• Use simple, direct language.

• Answer questions as directly as possible.

• Emphasize that they are safe, you are safe, and that you will take care of them.

• Validate their feelings by saying things like, “It’s OK to cry. I miss them too.” Statements like “Don’t cry,” or, “They wouldn’t want you to be sad,” do not help children process.

• Consider an activity, such as drawing pictures or writing letters, that can help you and the child feel connected to the person who died.

Riley reminds us that children may ask the same questions, over and over.

“This is how kids process things, and they are sometimes trying to verify the responses,” she said.

If you or someone you know is in emotional distress, Vermont operates a suicide and crisis hotline at 988, which can be reached by phone or text message.